Learn More

Architects of Change Summer Camp

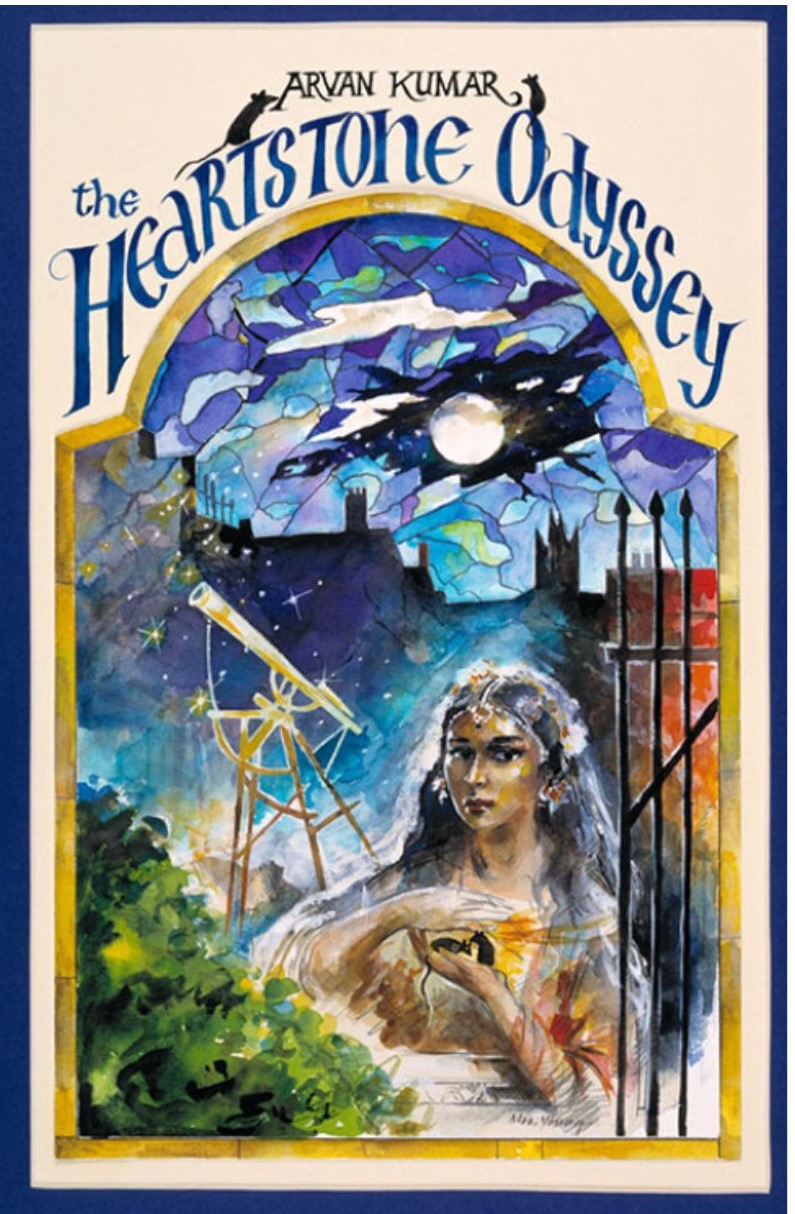

The Rosa Parks Museum's annual educational summer day camp, Architects of Change, is open to all River Region middle students who will be entering grades 6-8 during the 2025-2026 school year. The mission of the camp is to share the techniques of non-violent conflict resolution used by Mrs. Rosa Parks, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and other leaders of the early Civil Rights Movement. Our goal is to connect past struggles in the quest for equal rights to social justice struggles that continue today. This year's camp has been extended to two weeks in order to incorporate participation in the first-ever Heartstone Global Story Circle in the United States! This is a long-running program started in Great Britain in 2000 and has since spread throughout the U.K., Australia, and Kosovo (http://heartstonechandra.com/home/).

About the camp…

- Workshops on conflict resolution and building toward the Beloved Community.

- Training helps campers to handle conflict effectively and peacefully; embrace forgiveness, understanding, and acceptance and respond to conflict with reconciliation instead of lashing out or holding grudges

- Connecting past Civil Rights events to modern social justice issues through visits to civil rights sites

- The Heartstone Odyssey novel study and Global Story Circle program with a culminating art project

Field trips…(subject to change)

- Rosa Parks Museum and Children's Wing

- Walking tour of downtown Montgomery's civil rights historic sites

- Tuskegee University (including The Oaks, home of Booker T. Washington, and the George Washington Carver Museum)

- Tuskegee Airmen Museum at Moten Field

- Birmingham Civil Rights Institute

- Negro Southern League Baseball Museum

Fees and other important info…

- Located at the Rosa Parks Museum (Troy University Montgomery)

- May 26 - June 6, 2025, from 8:00 AM to 4:00 PM daily

- $100 per student (discounted rates for additional children within the same family)

- There are a limited number of scholarships available. (Please contact McKenzie or Donna for application, which is due no later than April 15th.)

- Breakfast, lunch, and snacks provided daily

- Non-refundable $20 deposit due with application no later than Friday, April 18, 2025.

- Balance due Friday, May 16, 2025

- Parents will receive camp itinerary no later than May 19th.

If you have questions or need more information, please contact:

McKenzie Walker, mwalker166145@troy.edu (334.241.9541)

Donna Beisel, dbeisel@troy.edu (334.832.7295)

Tired of Giving In: Rosa Parks and the Montgomery Bus Boycott Mobile App

FAQs

Examples of Alabama “Jim Crow” laws

- Hospitals No person or corporation shall require any white female nurse to nurse in wards or rooms in hospitals, either public or private, in which Negro men are placed.

- Buses All passenger stations in this state operated by any motor transportation company shall have separate waiting rooms or space and separate ticket windows for the white and colored races.

- Railroads The conductor of each passenger train is authorized to and required to assign each passenger to the car or the division of the car, when it is divided by a partition, designated for the race to which such passenger belongs.

- Restaurants It shall be unlawful to conduct a restaurant or other place for the serving of food in the city, at which white and colored people are served in the same room, unless such white and colored persons are effectually separated by a solid partition extending from the floor upward to a distance of seven feet or higher, and unless a separate entrance from the street is provided for each compartment.

- Pool & Billiard Rooms It shall be unlawful for a Negro and white person to play together or in company with each other at any game of pool or billiards.

However, it was fitting that the civil rights movement really began on a city bus because the “separate but equal” foundation for the Jim Crow laws actually started on a racially segregated train. In a famous 1896 case, Plessy v. Ferguson, the U.S. Supreme Court pronounced the separate but equal rationale, but of course, the facilities and treatment were never equal. Mrs. Parks remembers going to school in Pine Level, Alabama, where buses took white kids to the new school, but black kids had to walk to their school. “I'd see the bus pass every day,” she said, “but to me, that was a way of life; we had no choice but to accept what was the custom. The bus was among the first ways I realized there was a black world and a white world.”

Under Jim Crow customs, it was relatively easy to separate the races in every area of life except transportation. Bus and train companies often couldn't afford separate cars, so blacks and whites had to occupy the same space. Thus, transportation was one of the most volatile arenas for race relations in the South.

Ms. Robinson joined both the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church and its Women's Political Council (WPC), which had been founded by another Alabama State English professor Mary Fair Burks. Near the end of 1949, while boarding a public bus to go to a friend's house before going to the airport, Robinson was humiliated by an abusive and racist Montgomery City Lines bus driver who yelled at and ridiculed her for mistakenly sitting in the “white section” of the bus even though there were only two other passengers on board. Because of this incident, she used the WPC to target racial seating practices on Montgomery buses.

In 1960, after years of being targeted and harassed for her role in the civil rights movement, Robinson left Alabama State (and Montgomery), as did many other activist faculty members. After teaching for one year at Grambling College, Robinson moved to Los Angeles, where she taught English in a public school until her retirement in 1976. Robinson's health suffered a serious decline just as her memoir, The Montgomery Bus Boycott and the Women Who Started It, was published in 1987. She was honored with a 1989 publication prize given by the Southern Association for Women Historians but was unable to accept the award in person due to her poor health. She died in Los Angeles on August 29, 1992.

- Blacks would not ride the buses until polite treatment by bus drivers were guaranteed to them.

- Seating should be offered on a first-come, first-served basis.

- Black bus drivers should be employed especially in areas that were predominantly black.

When these demands were met, blacks would resume riding the city buses.

One month later, in April 1955, Aurelia Shines Browder was arrested for refusing to give up her seat to a white passenger. She was named as the lead plaintiff in the Browder v. Gayle case.

On October 21, 1955, Mary Louise Smith, and 18-year-old student refused to give up her seat on a bus to a white woman and was arrested on the spot. She was tried, jailed, and fined nine dollars. She was also a plaintiff and testified in Browder v. Gayle.

The Colvin incident roused the black community in Montgomery. The Citizens Coordinating Committee, led by local businessman Rufus Lewis, issued an appeal to the “Friends of Justice and Human Rights.” It denounced “certain legal and moral injustices incurred in the public transportation system” and offered the Colvin case as “an opportunity, in the spirit of democracy, and in the spirit of Christ, to deal courageously with these problems.”

Initially, Montgomery city officials were amused the demands of the MIA and the boycott and thought it would quickly fade out. After the first months of the boycott, they were not as amused as the boycott continued affecting Montgomery's economy. White downtown business owners began to feel the effects of the boycott as they were receiving less traffic in those areas. The bus companies began losing approximately $3,000.00 per day from lost fares. As a result, the bus company raised fares and terminated bus routes in many African American neighborhood to offset the losses. Many white families who employed black domestic workers (such as maids, cooks, etc.) were unhappy that they had to travel miles to carry their workers to and from work. On January 23, 1956, negotiations between Mayor Gayle, the bus company, and the MIA ceased. Mayor Gayle stated that there would be no more negotiations until Montgomery's African American citizens got back on the buses.

Once the white leaders of Montgomery realized these techniques were not working in getting people back on the buses, they turned their attentions towards the citizens themselves.

The social impact of the boycott was also felt throughout Montgomery. Even though many whites were upset with having to drive their workers, other white housewives were sympathetic to the cause and willingly drove their workers wherever they needed to go. Occasionally, as a way to try to stop the boycott, black were arrested for simply walking down the street. They often had things such as water and urine thrown on them as an intimidation technique. The boycott leaders also suffered. Rev. King's house was bombed in January of 1956, as was the house of Rev. Robert Graetz in August 1956. These tactics did not work, and the boycott remained in effect. Also in January of that year, Mayor Gayle and several other white leaders of Montgomery formed the local chapter of the White Citizens' Council (WCC) whose main goal was to maintain racial segregation. Mayor Gayle encouraged Montgomery citizens to not give in to the demands of the boycotters because they were “after the destruction of our social fabric.”

Furthermore, the Montgomery Bus Boycott started what would become known as the Modern Civil Rights Movement. Several of the boycott leaders, such as King and Abernathy, went on to lead other civil rights events. Many of the techniques of nonviolent resistance that were used to great success went on to great effectiveness in other civil rights events.